Musings on Public Discourse as it pertains to Present-Day Arts Funding

(©2012 Paul Madryga – All Rights Reserved)

[This is a bit of a dated document, so let’s put it in some historical context: at about the time of its writing in the Spring of 2012, a local arts organization were well-on with a very large project – one that, arguably, may well have been more than they were capable of handling at the time. They had gained no small amount of support (both financial and political) at City Hall, and were in the process of applying for some government grants at the provincial and federal level. To make a long story a bit shorter, their grant applications were denied – but their partners at the City found this out, not through direct contact from the leadership of the organization in question, but via the local newspaper. Suffice to say, City allies were not impressed, and neither were many potential supporters in the community. The project met its end a couple of years later, and the organization itself has since wound up operations – a victim of the COVID pandemic, certainly, but also, one could argue, of its own hubris. Should this article serve as a cautionary Public Relations tale to those in the arts administration business, so much the better. – P.M., 16 June 2025]

The recent public debate concerning governmental funding (or non-funding) of arts initiatives has given this guitar teacher some reason to think – the occasion of a six-hour drive to Saskatoon in early May 2012 gave him the opportunity to do so out loud (Yes, he often talks to himself on long drives – it’s one way of staying awake…). Once safely-ensconced in a B & B for the evening, he endeavoured to write up as much of that one-sided conversation as his fingers could recall… here’s what came of it.

The first point to make, crucial to the rest, concerns the financial reality of the Arts industry: artists on their own cannot support it – never could, never will. As a working artist myself, it’s crucial for me to remember how much of my success I have owed to non-artists who like the art that I make – the vast majority of people who would buy my CD’s, come to my gigs, and register their kids for guitar lessons in my program are not themselves trained artists. They’re art-savvy folks, certainly, who know what they like – but they are not artists.

Every era of high artistic accomplishment has had its core group of benefactors – artistically-aware non-artists with sufficient disposable income who give a generous amount of it to the Artist in order to enable said Artist to make Art. Michelangelo, Bach, and Handel (along with a huge raft of others) had the Church; Joseph Haydn and others were in the employ of blue-blooded families like the Esterhazys; Florentine artists in the Renaissance had the Medici family. If I may appropriate a term from J.K. Rowling, I like to think of these benefactors as Enlightened Muggles with Means – well-to-do people, schooled in the Arts to some degree, who have some financial wherewithal and who know what they like. In our day, there are university endowments (In addition to the support of my family, I owe a great chunk of my training to the posthumous generosity of a lady named Mary Smart, who bequeathed a tidy sum to the Brandon University School of Music); universities themselves (in Canada, at least) have a large amount of their costs underwritten and subsidized by that ubiquitous benefactor called The Government. Artists have a fundamental need for these Enlightened Muggles with Means; we simply would not be able to survive – never mind cover the costs of making the Art – by just making Art for one another! To sum up: 1) If there is to be Art, someone other than the Artist has to pay for it; 2) Art thus depends on the support of the non-artist with some spare cash (the Muggle with Means).

This takes us to 3): there is a Muggle Care Protocol that must be followed. The Muggle has to be carefully approached, befriended, and cultivated – their artistic sensibilities have to be continually nurtured, engaged, and just as importantly, informed. Once the relationship has developed into one where the Artist can approach (and hopefully re-approach) the Muggle for funds, they owe it to the Muggle to keep the latter abreast, in a prompt and honest fashion, of how the artistic pursuits are coming along – the Muggle claims a certain amount of ownership of the project, since they’re the one paying for it. Withhold information, and the Artist may be in the market for a new Muggle with Means very quickly – and good luck with that, because they tend to talk to one another about their Artists (The Muggles-With-Means Club is a small one, especially in a city the size of ours). If the Artist takes care of their Muggle, however, they could have strong, loyal support for many years.

How, might you ask, does all of this relate to recent dustups? Well, as discussed above, the Muggle with Means could either be a rich private citizen or corporation (Muggle as Mogul), or it could be a whole group of people who together have just enough spare cash for their leaders (i.e., politicians) to collect it and distribute some of it on their behalf to a deserving artist or two – Muggle as Taxpayer. Either way, the aforementioned Muggle Care Protocol still applies.

Governmental support for the arts isn’t a new phenomenon: artistic benevolence on the part of autocratic regimes and the non-elected ruling class has been around for centuries. In either of these scenarios, it was (and is) a fairly straightforward process: the artist gets money from tax revenue, but has only one or two patrons to please (aforementioned autocratic patrons being completely unanswerable to the poor saps who they tax). For the Artist in the modern democracy, it’s more complicated and precarious, since the extent of funding depends on the extent to which the Electorate wants the elected official to fund the arts. Enlightened Muggles would be fine with government money funding artistic excellence (and usually trust their Government Arts officials to decide what constitutes “artistic excellence”); an artistically-uninformed one would be more wary of it, since Ignorant Muggles tend to fear that which they don’t understand (Who remembers the “Voice of Fire” debate from a decade or so ago? Look it up – it requires a discourse more detailed than I can offer here, but it’s worth a read). That, alas, is democracy at work – millions of potential patrons, each of whom are entitled to an opinion (since they justifiably consider public money to be _their_ money), but only a few whose opinions are informed ones.

Of course, it’s not the elected official who actually doles out the Art money (although they doubtless have no small amount of influence on the proceedings); it’s the art-savvy bureaucrat (well, a team of them, advised by working artists in the relevant field) in charge of the governmental body/program processing the funding application. The Muggle as Bureaucrat, being an non-elected official, is not directly answerable to the Electorate; however, they are answerable to someone who is – The Muggle as Minister of Arts, Culture, Heritage, or whatever. Since they both want their jobs back after the next election, they’re going to pay very close attention to two things: 1) how much money they’re being asked to grant, and 2) what the Electorate have to say, informed opinion or no, about what is or is not quality art. I believe it’s called Knowing Your Base, a.k.a., Dancing With the One That Brung Ya.

And so a subset of the arts community can find itself in the situation where there are many legitimate opinions, but not many informed ones; several folks feel left out of the conversation, and some opinions get interpreted as personal attacks, in which the character, rather than the argument, of one proponent or critic of the artistic initiative becomes the target. It makes the Artist question the motives of all critics, and overlook any possible legitimacy of the criticisms. Unfortunately, this is a condition commonly-seen in Muggles who haven’t been properly cared for – remember the part about keeping them informed and engaged?

Solutions to such a situation aren’t easy – all I can offer at present are advisories for the future, should this conversation arise again. The first is to consider foregoing public funds altogether in favour of grooming the private and corporate Muggles with Means. It takes a considerable amount of effort to establish and cultivate these relationships, but it would mean that the Artist would in no way feel beholden to those who in their view constitute an artistically-uninformed Joe Q. Public, since no public money would be at stake. The Great Uninformed could gripe and complain all they want about Art that they don’t understand, and it wouldn’t matter in the slightest. The Artist makes Art the Artist’s way, and provided that the Artist’s well-heeled Muggles like it, everything’s fine. Who knows? Some of the Great Uninformed might just sample the art, and find it to be not so bad after all…

The second advisory is to seek public funding again, with an important caveat: as the Artist, you must continually inform and update the public partners, and always, always be completely honest with them – like the aforementioned private and corporate Muggles, it’s their money. Some will appreciate the effort you make at keeping them fully and honestly informed; they’ll feel like a partner with some ownership in the process and grow from it artistically. Trust them with that ownership, and that trust will be repaid in loyalty – in the music industry, this is called Audience Development. It’s disheartening when a small but vocal number throw it back in your face and oppose you with under-informed opinions. In the end, there’s little to be done about this, other than to rise above it – let’s face it, there are some Muggles who are beyond care, and you simply won’t reach them. You can’t control what they say, but you can control how you react to it. Accept that there will be slings and arrows that come with seeking public money, or don’t bother seeking public money.

.

.

The Keeper of the Time:

Preventing the Onset of Metronome Phobia

(©2006 Paul Madryga – All Rights Reserved)

Part 1 – “Be Afraid… Be Very Afraid…”

“A What’ronome..? Oh, that thing… Man, they’re scary…”; “It makes me frustrated…”; “It just confuses me…”; “The Clicky Box! Noooo! It’s Evil…!!”; “I think mine’s broken – it keeps speeding up and slowing down…”

I have to confess to there being a time in my teaching life when I’d hear these quotes often, much to my discouragement: I was striving to foster a desire in my young charges to play at the best of their ability, in order to extend it; I wanted to nurture their self-confidence in a safe yet challenging environment, and I knew that the metronome would eventually play a crucial role in the development of this environment:

– It reinforces the concept of a steady external pulse (One that usually doesn’t square with the student’s natural internal pulses), which enables competent and confident playing in both solo and ensemble contexts;

– It allows for a gradual progression in speed and velocity, and gives teacher and student the means to monitor and assess ongoing progress;

– When used right, it allows the student to feel every necessary motion in the fingers, arms, and shoulders in a steady, flowing beat, enhancing his/her physical sense of beat subdivision.

The justifications for regular metronome use are manifold – the fact that you’re reading this article suggests to me that you don’t need them. It can be frustrating for all involved, therefore, when the metronome experience isn’t nearly as successful as we wish it to be: at one time or another, I was making one of three mistakes, all of which contributed to my students’ fear of using the metronome (a condition that I’ll call, for lack of a better name, Metronome Phobia):

1) In the interest of preserving the aforementioned safe environment, I left the metronome out of the picture entirely, thus leaving the student unexposed to a tool that will develop his/her ability in a way that no other tool can;

Or:

2) I introduced and used the metronome in such a way that caused sufficient fear and frustration that the student would approach future metronome contact with apprehension. S/he failed to experience a feeling of early success – worse, s/he took a memory of failure away from the experience. Relieving some students of that baggage has been a long process, and not a particularly happy one for all involved;

Or:

3) Both of the above – in some cases, I left it out of the picture for too long and then introduced it in a “too much, too fast” manner.

The disparaging words directed at my friend the Metronome were coming hard and fast – the metronome, being just a box with a battery, was unfazed, but I was starting to get a bit down on myself about it. I Googled the keywords “metronome” and “success”, and the phrase “how to use a metronome” – I found a virtual metronome online, and many, many sites that offered to sell me a real one. Suffice to say, these sites were not immediately helpful (I already had a metronome, thanks). I also found several articles on-line that addressed the importance of using a metronome when practicing. The basic message of these articles was, “Get a metronome and use it!” Again, not particularly helpful, for the simple reason that anyone sufficiently in the know to look for such an article doesn’t need that message.

A few other articles give the reader a succinct yet accurate idea of how to use a metronome successfully: in a ten-line article on her website, a banjo player named Angie Sumpter provides a valuable insight, that being to learn to play evenly and smoothly on a quarter-note pulse before trying to subdivide it – this insight is shared by several other commentators online, but this is hardly an in-depth analysis, and neither she nor they seemed to address the issue of why the metronome can be such a scary thing for young musicians in the first place.

Happily, my program’s metronome journey, while still ongoing, has been a positive one of late. I found myself with a large chunk of free time while waiting for a train in Minneapolis this spring, so I figured that it was time to get some of my thoughts on this journey down on laptop…

Before getting into the “how-to” of metronome use in practice, it bears considering why we practice in the first place. Those of you that have read Ed Sprunger’s book Helping Parents Practice will certainly know the answer: we practice to make whatever we’re playing feel easy. This suggests to me that if whatever we’re practising feels hard, we’re either doing too much, or doing it too soon, or doing it too fast, or a combination of all of the above. If we haven’t yet found a way to make it easy, we need to spend more time seeking that means of ease.

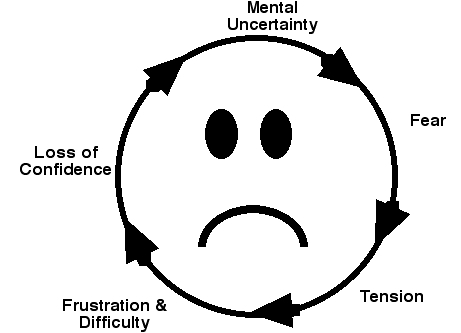

I find this an insight worth dwelling upon before seeing how it applies to our friend The Clicky Box. I think it’s fair to say that the student who utters any of the quotes that begin this article is experiencing a degree of mental uncertainty – during practice, mental uncertainty is dangerous, because it causes fear. Fear teaches our brain how hard something is by manifesting itself in the muscles in the form of tension. Tension makes what we’re doing harder, not easier, and nurtures a mindset of frustration and difficulty. This, of course, is cyanide to the student’s confidence, and certainly won’t improve his/her mental clarity. An unfriendly circular situation has developed:

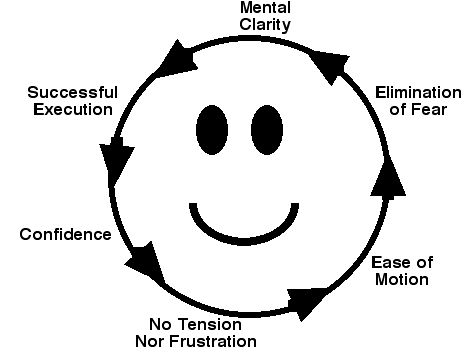

It occurs to me that we should strive to make the circle spin in the opposite direction: Having a clear mental idea of the task that s/he wants the muscles to execute (no matter how small or slow that task is) helps the student successfully accomplish the task with confidence; this success precludes the onset of muscular tension and mental frustration, makes the task feel easy, and above all, eliminates the fear – and so the circle of success continues:

There’s no questioning the rationale of practice as a means of making a passage easy. I think it fair to say, moreover, that a deeper goal towards this end is to eliminate the fear that inhibits this ease: as musicians, we practice to eliminate fear, and encourage our students to do the same. Under no circumstances should the metronome (or anything else in our practice, for that matter) be a source of fear – rather, it should be a part of the solution to fear.

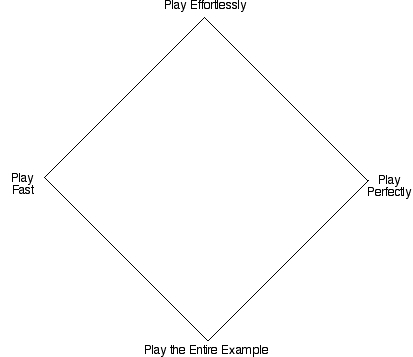

In his book Effortless Mastery, jazz pianist Kenny Werner emphasizes the elimination of fear, via his concept of the Learning Diamond. The uppermost corner of the Diamond is Effortless Motion; the three lesser corners are associated with Speed, Size of Excerpt, and Accuracy.(1)

According to Werner, we practice a passage or technical concept in order to reinforce the relationship between the four corners, but only with a mind for three corners at a time, one of which must be the Effortless Motion corner. If a passage is difficult, eliminate one of the other three corners: play it as slowly as necessary (which I interpret to also allow for as flexible a pulse as necessary) in order to get all the way through with correct pitches, rhythms, and fingerings; play as small a chunk of the passage as necessary in order to get the correct pitches, rhythms, and fingerings at tempo; or (as a preparation for the performance mindset, and as a reward for an extended period of hard work), trust your fingers to get all the right pitches at the right times, play the whole passage at tempo, and accept the ensuing result for what it is, whatever happens.

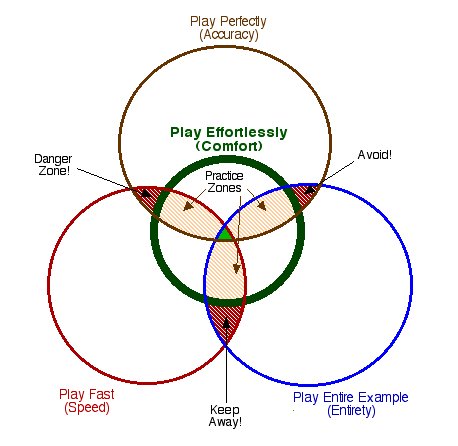

I read Effortless Mastery at a time in my Masters’ study when I really needed a change in mindset, and Werner’s Learning Diamond resonated with me – so much so that I turned it into a Venn diagram:

The reader will notice that the bold-edged Comfort circle is central to the whole concept: this is the Primary Field. Working in the dark zones outside of that field is defeating the purpose of practicing. The best results are found in the lightly-coloured Practice Zones, where any two lesser circles intersect with the central circle of Effortless Motion. These are the zones where the most work gets done with the least amount of fear, and these are the zones in which the student needs to stay in order to nurture confident growth, because these zones constitute the pathways to the centre of the diagram, the coveted Performance Zone, where all circles converge within the Primary Field of ultimate confidence and comfort. If something is causing the student to leave the Practice Zones and veer into the dark areas of the diagram, then whatever it is needs to be either repackaged, broken down into its component steps, or removed from the picture altogether until such a time that the student is able to process it.

Next Installment: How does the metronome fit in to this picture?

Part 2 – Packaging for Student Consumption: “Do” before “Think”

The previous half of this article dealt with the rationale of why we practice, and some general thoughts pertaining to the elimination of fear. The second installment incorporates these thoughts into making day-to-day metronome use a positive experience.

When I did Book 1A (and other training units) with Frank Longay, he impressed upon us young teachers the importance of Experience preceding Concept – in other words, Make it a Body Experience before a Mind Experience: get the child to execute a task before saddling him/her with the intellectual burden of the task. With that in mind, I’d like to share some ideas for metronome introduction that have come to me over the past few years via training units with numerous Suzuki pedagogues and on-the-ground experience…

To start, it’s worth noting that there’s a great deal of pre-metronome work to be done – to once again to defer to the wisdom of Ed Sprunger, “I don’t encourage students to play with a metronome until they can really sense the pulse in their bodies.”(2) Pulse progress can be made with various activities that help the student to feel a beat – any beat – in his/her body, and begins before the child even starts to play. The human body has its own sense of pulse, which has little or no relevance to any pulse beyond it. Turning an external beat, regardless of the source, into a body experience is a good place to start:

– Echo-Clapping, à la the My-Turn-Your-Turn Game – Twinkle rhythms, of course, are especially relevant here;

– Clapping the rhythms of the early repertoire with the CD

– Marching around the room to the CD can be good fun, too!

The Body Canon activity came into my teaching repertoire after a workshop with one of my choir mentors, Elizabeth Grant, who uses it as an activity for reading development. The teacher carries out a series of rhythmic motions somewhere on their body (clap twice, tap the head twice, two knee-pats, etc); the student repeats the actions of the teacher, two beats behind them. Pretty soon, the teacher can add the extra challenge of a gradual accelerando.

When you think the child or class is ready, add the instrument to the rhythmic picture. The Ball-Bounce Game is a favourite of my Pre-Twinkle/Book 1 guitar class (Many thanks to Frank Longay for this one): play an open G when the teacher bounces the ball. Once that’s easy, let the ball bounce for gradually a little longer. In addition to working in the idea of an external beat, it also begins the development of ensemble ability, and helps teach the child’s fingers and brain the important skills of timing and anticipation.

Depending on the child and the group dynamic, many of these activities will need an extensive period of reinforcement before you’re ready to turn on the metronome. Once the kids start looking bored with them, it’s a good time to up the ante and start the Clicker clicking:

1) Walk or march around the room to the beat – pick a tempo to which the child can easily walk (something close to his/her own walking pace).

2) Echo clapping, Stage 2: “make the clicks disappear” (A tip of the hat to guitar trainer David Madsen). The teacher claps first, and then the student. After the child’s first attempt at this game, the teacher, in the interest of staving off Metronome Phobia, must smile and say, “That was a wonderful attempt! Let’s do it again!!” – no matter what the child’s first attempt sounds like! In my experience, quick tempos are more forgiving that slow ones (I’ve heard this attributed to the child’s quick heartbeat – at any rate, the margin of error is far less noticeable at the faster tempi), and short rhythms are easier to echo than long ones, so start with easy-to-duplicate four-beat motifs (Twinkle rhythms rule here, of course) at a setting of about 120 or so, and work your way longer and slower from there.

3) Once #2 above is sounding secure, give it a shot while walking in place (“put the clicks in your feet”), and then, for finer motor-skill development, while toe-tapping to the beat (“put the clicks in your toes”). Again, the guidelines of “faster, shorter” before “slower, longer” apply.

4) Body Canon makes a return, except with the help of a parent or older, more experienced student who is your “assistant”: start at a comfortably-slow tempo, and have said assistant gradually edge the metronome faster.

5) When it comes time to put the clicks in the fingers (or bow, or facial muscles, depending on the instrument), I’ve had success with the Pass-the-Note game – some folks might call this Musical Ping-Pong, and works best when introduced in the pre-metronome stage: the teacher and student play the same note back and forth on the metronome for a spell, until someone falls off the beat (or “misses the ball”). This can evolve into a Ping-Pong version of Moonwalk (for guitarists – teachers of other instruments can insert their favourite Pre-Twinkle song here), and eventually the opening notes of the child’s early repertoire.

6) It bears reiterating that metronome work should always be done in the student’s comfort zone. The idea here is to expand that comfort zone. By the time the child attains the 5th level of comfort noted above, s/he is ready to start using the metronome as a tool for review: start with the Twinkles (one variation per day on the metronome – if that’s too much, then do a variation in chunks, as small as necessary to ensure success, with “thinking moments” inserted as needed), and work your way up. This also helps the student develop the discipline needed for daily technique practice, with which the metronome will help for systemizing and gauging progress.

Some final thoughts on the Metronome:

– I tell my students the obvious (and not just for comic effect, although it does elicit the occasional giggle): make sure you switch on the metronome! I know it’s a no-brainer, but I think it bears mentioning regardless. I tell them that using a metronome is like doing dishes or exercising: once you’re over the initial barrier of starting, it’s not that bad – after a while you don’t mind it, and it feels great when you finish!

– Use it as much as possible, in such ways that guarantee success:

– Small chunks are more manageable than big chunks;

– The bigger the chunk, the slower the tempo;

– Problems with subdividing? Double or triple the click speed – let the metronome subdivide for you for a while;

– Know when to turn it off! You, not the metronome, are the boss – you have the ultimate control of the “off” switch.

Think of your best, most trusted friend: you can always count on that friend to be honest and forthright with you, but sometimes you don’t want that kind of blunt honesty. However, there are other times when you find that friend’s company to be just what you need. The metronome is incapable of lying – that said, you’re not going to take your metronome out for coffee anytime. It’s a tool that you own – but it does not own you!

If the metronome is becoming the source of (as opposed to the solution to) frustration, shut it off and save it for tomorrow.

The ultimate goal as I see it is to develop the comfort zone sufficiently to allow the student to use the metronome during the learning phase of a new piece. This is where metronome work really starts showing its worth – to quote Dr. Sprunger again: “What metronomes can do is help you organize the learning process.”(3) Now that the fear has been dispelled, weekly tempo goals can be written in the music at specific teaching spots and/or on practice charts; as mentioned, students can also gauge their progress in their technical regimens. Additionally, the metronome can now take an important place in the Practice-Circle scheme of things, helping the student move his/her repertoire, one chunk or phrase at a time, one notch at a time, towards the Performance Zone. The student must be guided through the process of reaching that Zone, and the metronome is crucial to this process. The more often the student makes that trip, the easier the next journey there will be. I’m happy to report that I’ve not heard any disparaging words about my friend the Metronome in quite some time….

Footnotes:

1 – Werner, Kenny. Effortless Mastery: Liberating the Master Musician Within. New Albany, IN: Jamey Aebersold Jazz, Inc., 1996, pp. 161-2.

2 – Sprunger, Edmund. Helping Parents Practice: Ideas for Making it Easier, Vol 1. St. Louis, Ann Arbor: Yes Publishing, 2005, p. 215.

3 – ibid.